As I prepare to leave Tsu city, there are a lot of thoughts rumbling in my head. It may be inspired by the rumblings in the over laden sky. I look out at the turbulent sea while waiting for “Phoenix”, the super ferry that will take me to Chubu centrair. I have an hour or so to kill and I wait along with a dozen others who do not comprehend any other language but Japanese. Yet, I feel perfectly at home. Everything about this place reminds me of home, well a cleaner home of course. I always try to ruminate about my experience in a new country like every seasoned traveller would do in order to make sense of it all but with Japan, I know not where to start.

My first Japan visit was in Spring 2006 and that visit left an everlasting impression in my mind. Japan always beckoned. And today, after my second visit to this country I know why. The people don’t speak English, they don’t give a damn but even though they don’t understand you or speak your language they are extremely genuine. They still want to communicate with you, go out of their way to help you out, be a friend not a foe. During this visit, I visited a small grilled meat bar twice. The owner didn’t speak a word of English but his smile was one of the most genuine ones I have seen in my last two years of sojourn in the Western world. Here, people are happy. Even though they probably work around 60-70 hours a week, in the end they come back home to a family, they come back home to warmth. Nothing has ever stood in between the Japanese spirit and sprite. Not the earthquake, not the tsunami. Life goes on pretty much through all these calamities, a point I had realized early on in my school life when writing an essay on India’s achievements post Independence in tandem with Japan’s achievements after Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Japanese are highly resilient with the soul of a phoenix.

Japan has also been particularly appealing to me because of the Haruki Murakami connection. Japanese authors have been a favorite. Murakami, Kashuo Ishiguro, Yukio Mishima have all been bedtime companions during my adolescence. Like Murakami says in Kafka on the shore, “Even chance meetings are the result of karma… Things in life are fated by our previous lives. That even in the smallest events there’s no such thing as coincidence.” Maybe my two trips to Japan in the space of six years is no mere coincidence.

Six years have passed since my last visit, not much has changed. The cities, Tokyo and Kyoto have got more populous. The trains still run impeccably on time. People are still genuinely happy. The Buddhist temples still retain an air of mystery shrouded by an aura of the divine. Here, one can find peace, real peace. Amidst the fast, busy, day-to-day existence, there is something stagnant about the Japanese. As if they know how to truly live. Or as Murakami says in 1Q84, “Being alive, if you had to define it, meant emitting a variety of smells”.

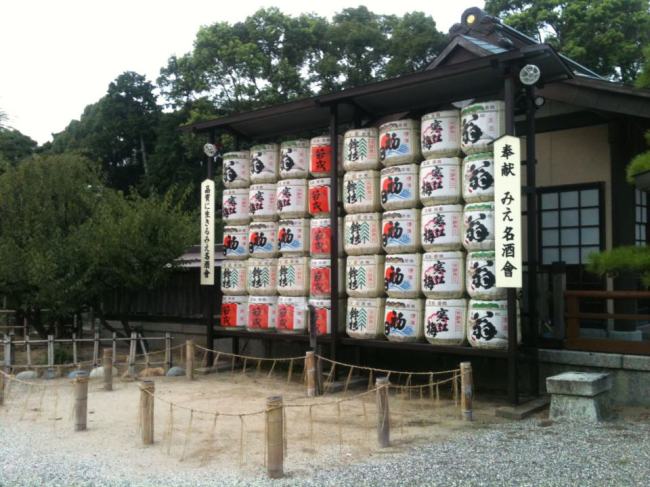

Nihonshu - sacred Sake barrels at 明治神宮 (Meiji Jingu shrine).